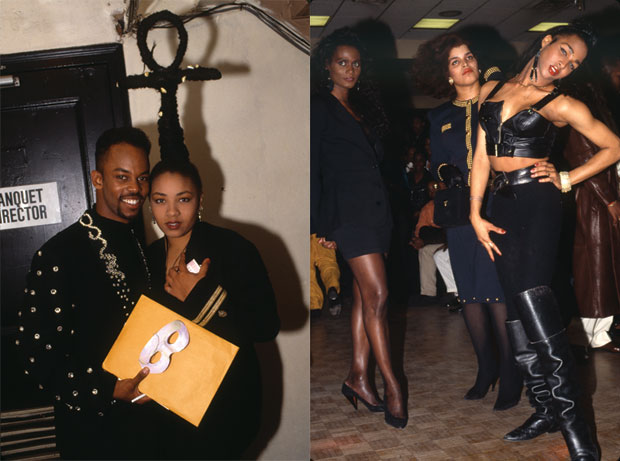

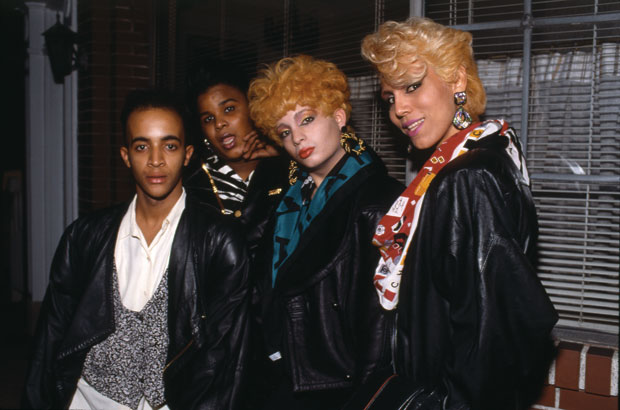

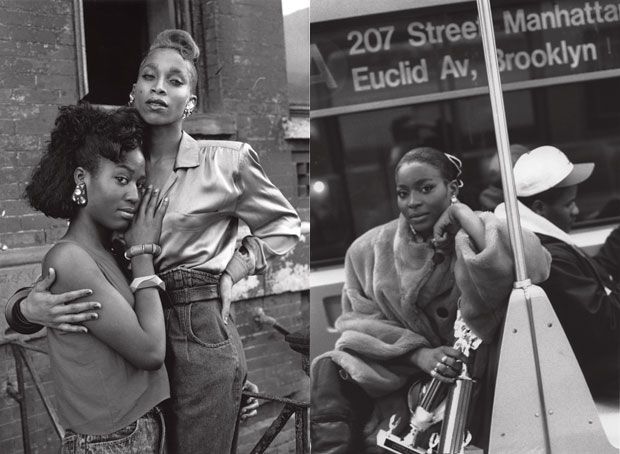

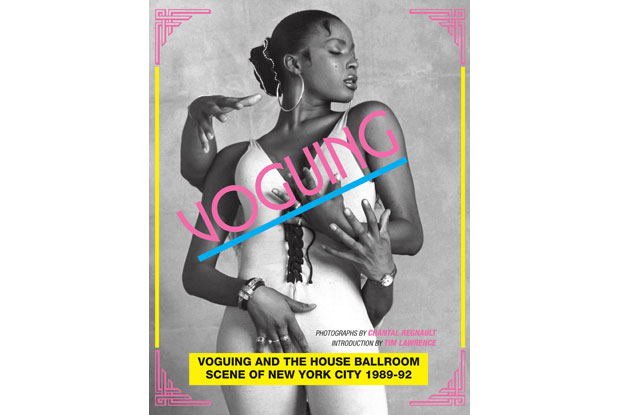

In our FADER Issue #56 feature "Face Time," we caught up with the next generation of the New York Vogue scene in all its fitted-baseball cap, baggy-jeans, hip-hop swagger. For a look at the legendary bygone era of Voguing, photographer Chantal Regnault's book Voguing and the Ballroom Scene of New York 1989-1992, gives us a three-year look into the ballroom scene at the height of its glittery heyday, through both images of glamourous posturing and quiet, day-to-day moments. We spoke with Regnault, who's French, about life in 1980s New York City, how she got wrapped up in the ballroom scene, and what the legendary queens were really like. Voguing and the Ballroom Scene of New York City 1989-1992 is published by Soul Jazz Books.

How did you end up documenting the ballroom culture in 1980s New York? I moved to New York about 40 years ago and my academic background was in literature. I was supposed to run in that direction but New York City triggered this desire for photography. There was a natural energy on the streets [of New York in the ’80s], and because I started out taking photos on the street, I was drawn to emerging sub-cultures. At the time there was breakdancing and graffiti, which in a way, led me naturally to the voguing scene to the ballroom scene. It was great fun.

Other than you and Jenny Livingston, who directed the documentary Paris is Burning, was anyone else documenting the scene at that time? Not really. It attracted some mainstream attention, so once in a while magazine photographers would come by, but there were not that many people were capturing the scene. There was this one guy Bryan Lantelme, he did the whole series of portraits of Drag Queens. But he was mostly documenting the scene at Sally’s Hideaway, a famous drag queen bar in Times Square— back when Times Square was not yet “Disneyland.” He did these gorgeous photos, but it was never really published, they’re on his site. It was more like a studio thing of the Queens and he would come to the ballrooms to get acquainted with them. But he was not really documenting the balls.

As a French woman heavily embedded in this predominately Black and Latino underground scene, did you ever experience any type of hostility as an outsider? Were you willingly accepted? I don’t like to photograph where I’m not welcome. But this was not the case, and I was really enjoying the scene. I could not have spent so much time if I was not perfectly welcomed there. People were very nice, and it was part of the glamour you know. You had to have a photographer. The photographer was the very proof that all this creation and inventiveness and originality was appreciated. So you were appreciated as being someone who appreciated what they did. It did not matter that you were white and straight.

In the press, you've said that, overtime, you really became enamored with the Femme Queens. Tell me about your relationship with them. It was a whole trip for me, you know? Being a female and being surrounded by all of these men who were incredible women, certainly more feminine than I was. There was an element of fascination in it and reflection on what all of that meant. It was vertiginous in a way, I completely forgot that they were men most of the time. The [queen] on the cover, we lost contact with each other in 2005, and when I started the book I was told that she was dead. And I said, Oh my God, another one, but I finally found out that she was alive but underground. She had become a Jehovah’s Witness and cut the Ballroom scene completely from her life. In fact, the queens that are alive, whom I knew back then, eventually went through sex changes and are not willing to involve their past life in the present because it has been so hard for them. They’ve gone through so much mentally and physically to really achieve the image of what they feel they are and now they are functioning socially in the bigger world and they don’t like to be reminded that they were once a man passing for a woman.

I remember watching Paris is Burning and thinking that it was really triumphant, but it was also very sad. Yes, there was a sad element to it, in that they lived in a very closed world. There were very few venues for them to be accepted in the bigger world. One of the elements of my friendship with them was that I was a straight person who dealt with them like a normal person and not like they were freaks. And that made them feel good—they’d come to see me, stay at my place, talk and shout, smoke a spliff together, tell me their stories. Their lives were pretty rough. They were night workers and constantly in danger—in the movie, you see one of them is killed. That was a common fixture.

Was there one person in particular that you really enjoyed photographing? I noticed there’s a lot of Octavia St. Laurent and Pepper LaBeija in the book. Pepper LaBeija, Freddie Pendavis— I have a little glimpse of Angie Xtravaganza in the book. I have Paris Dupree and Dorian Corey. The legendary girls who were coming from the stage and initiating this whole concept of the gay houses of couture. I’m glad I had a chance to photograph the iconic mothers who are all gone now.

All images are courtesy of Chantal Regnault from the book Voguing and the House Ballroom Scene of New York City 1989- 1992, published by Soul Jazz Books.