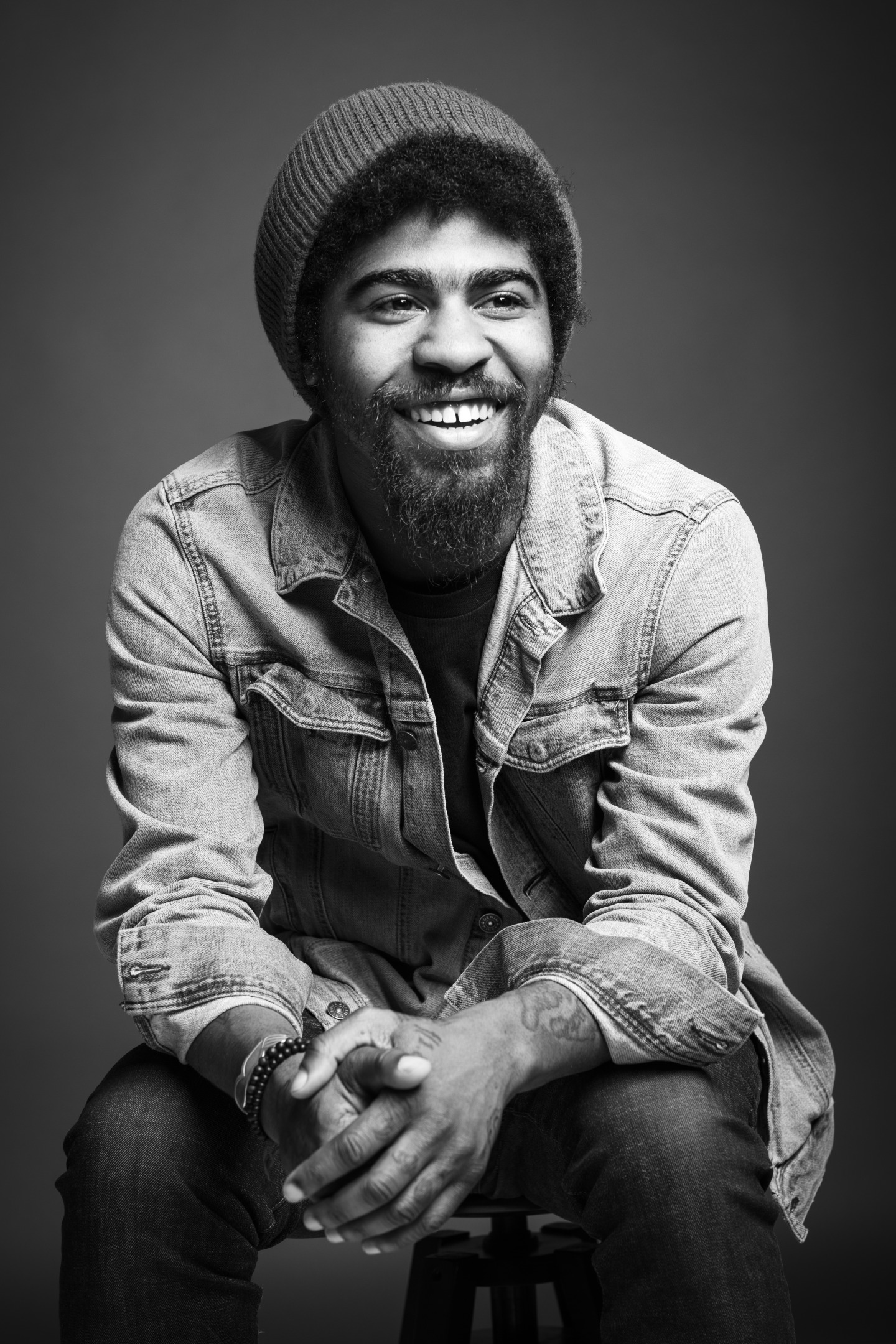

Devin Allen’s photographs are vivid love letters to Baltimore

With the release of his first book A Beautiful Ghetto, the artist is dedicated to showing his city’s unsung strength and plurality.

FJ Hughes

FJ Hughes

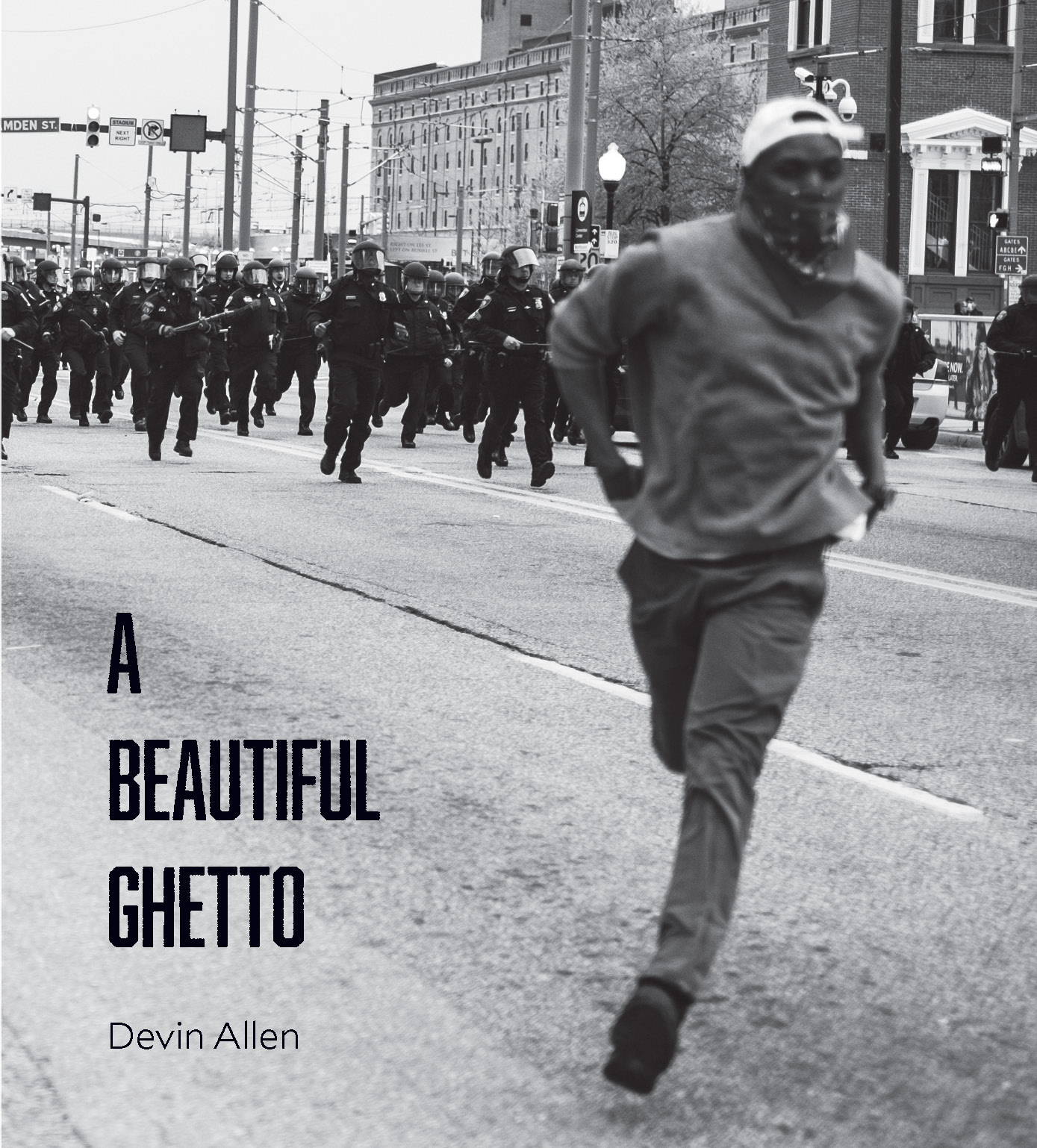

Baltimore photographer Devin Allen is dedicated to fortifying his hometown's legacy with his images. In 2015, a historic uprising emerged in response to Freddie Gray’s death at the hands of the police. In the midst of the impassioned protest, Allen captured a black-and-white image of a man evading the approaching line of policeman who stormed the streets armed with clubs. The next morning, Allen’s photo was on the front cover of TIME Magazine.

This September, he published his first book, A Beautiful Ghetto. It's a poignant offering that captures both the beauty and struggle of his hometown with poems, essays, and Allen’s own vibrant photographs. His personal relationship with Baltimore gives him the lens to document black life with a thoughtfulness and nuance that is missing from many depictions of the city. To celebrate A Beautiful Ghetto, Allen launched an exhibit with the help of theGordon Parks Foundation as the organization’s inaugural fellow.

The FADER spoke with Allen about giving back to Baltimore’s youth through his educational photography program Through Their Eyes, the importance reclaiming the narrative of black folks, and how taking pictures in Baltimore put him in touch with his emotions again.

Tell me about the birth of the book A Beautiful Ghetto.

I wasn't planning to do a book but that just kind of came into itself on its own. In Baltimore I was already documenting everyday life. Everything went so quickly from uploading that image that made it to TIME and then doing a show in Baltimore in July. To me, the show was good but it wasn't raw enough and it didn't tell the full story. I wanted to show people everyday life and the things that they don't see. It's usually, "Baltimore has 300 murders a year" or its called "The home of The Wire" or “The murder capital of the United States.” That's all they know about us. A lot of people didn't really know anything about Baltimore until the uprising, and then they went back and watched The Wire. For me, it was how can I tell the story about my city and Freddie Gray.

Some of the images in the book are from 2014 and 2015, before the uprising. It's tough here in Baltimore. You have those moments where you hate it and love it. Sitting on the stoops with your homeboys and just vibing is an energy that isn't articulated in anyway shape or form. I wanted to show those positive moments and everything in between that Freddie Gray may have saw or that I saw. The book is basically a love letter from me to Baltimore and how I feel about it and the uprising. And it's also a collaboration between me and my friends. When I did my second show in Philadelphia in 2016, it was the first time I had full creative control. I wanted to make people feel happy and then I'd want people to walk into another room and it fuck your head all up.

Devin Allen

Devin Allen

The first room was a “Beautiful Ghetto,” where you see row houses, dirt bikes, kids riding in the street. I'm playing music from Gil Scott Heron, Nina Simone, Kendrick Lamar. Then there was another room where I played the Freddie Gray video on a loop, non-stop. If you're looking at the photos you just hear him screaming, "My leg is broke."

People were crying. Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, who wrote an essay for the book, came up to me at the end and said, "This show is incredible. It needs to be a book." I thought it’d also be a great opportunity to include people in my peer group who inspire me. So, I reached out to Wes Moore, we were both on Oprah at the same time. Then I reached out to Keeanga because her book From #BlackLivesMatter to Black Liberation, was great and she has a unique outlook on the movement. I had my mother in the book and it was so special and have her talk about her life in Baltimore, through various eras, up to the point of having a son. I tried to say the least possible and include perspectives from people like Tariq Touré because he's a black Muslim from Baltimore. I didn't want the short essays to overpower the photos. I want the images to touch people but I wanted folks to come to their own conclusion.

We see these images of outrage and plight all around the world. Those are somewhat sensationalized when it comes to black communities specifically. How are you reclaiming that with your work?

For so long, we allowed outsiders to tell our stories. The goal of the book was to reclaim the narrative of our community and one thing that really inspired me was along the way I met some amazing people. I didn't even know what I was doing was that important. I was just putting my heart out there, but I watched a film called Through the Lens Darkly about black photographers and how our images are not controlled by us. If you look at the textbooks and how it start at slavery and don't talk about any time before that. They give us a month and they only talk about certain people. You look at slavery times when they'd take photographs of black people to create stigmas to say that black people are brutal or that we lack intellect. Our people have always been intelligent and also in our communities in these beautiful ghettos, it's hard to love something when we're barraged with the messages that tell us not to love it. Then when you don't love it, someone else loves it and then it gets gentrified.

People say, "You'll march for Black Lives Matter but you won't march for your people killing each other," but we do! Y'all just don't see it. We had a huge fire march here, we have these town hall meetings but people don't see it because they don't care. Those are the things that I want to show and bring back. Photography is very powerful and it can teach us how to love our own people.

While you were taking the photos of the community over the years, how did you emotionally deal with the harsh reality of some of the images and the pain that created them?

I lost a boatload a friends. A lot of the people in that book are my friends. If you're from here, you've lost something. I buried a lot of friends, and I don't even cry anymore. Documenting that actually started to give me more emotions back. I'm seeing how the world works and loving the simple things. Growing up, I didn't plan my life past 21 years old and I didn't respect my own people. When I was young, I was fighting all of the time. You had to be tough here, you couldn't be a punk. You'll mug another brother in the club before you speak to him. You step on somebody's shoe, it's an issue.

Photographing all of these black men made me also really love my brothers. Usually, I wouldn't speak to a dude I don't know. Now, I'm understanding that we're all one and it's a certain type of oneness that's been lost over time. We can point the finger at so many things but we can rebuild that. Yes, crack, heroine, AIDS, and lead case poisoning have all ripped through our communities. There's the lack of funding in schools and when people are disenfranchised that creates stress. I'm 29 years old and I've buried over 20 friends. I might suffer from post-traumatic stress [disorder] but I don't know. So I'm reclaiming my emotions and my spirituality, even more through photographs.

Devin Allen

Devin Allen

Devin Allen

Devin Allen

“Photography is very powerful and it can teach us how to love our own people.”

Is there a photograph that's a part of the exhibit, that stands out to you? One that's etched into your memory?

Photographing someone and then finding out that they passed away is the craziest thing to me. There's a picture of a guy named Rico who has his hands up and he was kind of leading the march. He was from Gilmore Homes and then I found out he was shot and killed. The way he led the march, I had to go up to him and shake his hand. I had respect for him and the words that he spoke so peacefully after the death of Freddie Gray. He actually knew him.

Or there's another photograph of a guy named Telly, the called him Mr.103 and he's from down the avenue. He has a fist up, with his hat on backwards, with a white T-shirt. When I got the book, I was pumped to go around his way and show him that he was in it but I never got to show him because he got killed. I'm helping keeping these people's stories alive. The reality is you could be here and then gone tomorrow. We have an Instagram page in Baltimore called Baltimore Murder Inc. that tracks all the murders and who killed who. You check it every morning to see if any of your friends or family are on there.

Devin Allen

Devin Allen

What was your reaction when you first saw A Beautiful Ghetto on the door of the Gordon Parks Foundation at the exhibit opening?

I tried not to cry. But it was so overwhelming. A lot of people don't know who Gordon Parks is, so when I show them his work they realize they knew it all along. I don't think people understand how powerful he was. It wouldn't be a lot of us shooting if he didn't open up those doors. They've allowed me to take things to the next level and also continue to chase my dreams. But, to have a show and be the first fellow is a big achievement. It's about keeping these doors open for the next person that comes behind me from my community. My foot is still on the door like, "Come on in." I'm still soaking it in. I’ve given my camera away to a person who couldn't afford a new one. The first day I met Swizz Beats he gave me a camera. That was the most inspiring moment for me for someone like him to the vision to invest in me when he probably didn’t plan on it.

Tell me about your program Through Their Eyes. You’ll be investing into that with the award from the fellowship.

Russell Simmons helped me start it in 2015. I didn't know anything about teaching but I just hit the streets giving out cameras for free. Mentoring some, doing art shows with some, and then I started working with kids with autism and intellectual disabilities. I've been working with them for the past couple months and helping them to express themselves. The way the world is, you can open up a small business very easily with the role of social media. So, I'm showing them how I went about things and got to the point that I did and I just want to make spiritual deposits to the youth how Parks did. He didn't want his vision to die with him and that's why he has the fellowship. I want to do the same thing, and do the legwork for Baltimore so that someone could keep this legacy alive.

What do you want the youth in Baltimore to learn about not only photography, but their city and themselves?

If you come from Baltimore you can survive anywhere. I feel that way with any ghetto, from Philly to Chicago to Florida. With the adversities that we face, we can accomplish anything if we put our mind to it. My legacy is love where you're from and if you want to make change and make Baltimore a better place for our kids, we have to do the leg work. We can't just accept it. You can make change with your own hands but you just have to get up and do it. I'm proud to be from Baltimore. I want everyone else to feel proud. It's a place that's still thriving and we don't lay down. You can't get rid of us.

Devin Allen

Devin Allen