Colson Whitehead On Writing, Slavery, And The True Origins Of America

The author’s latest book, The Underground Railroad, forces readers to confront America’s original sin — slavery.

Photo by Maddie Whitehead

Photo by Maddie Whitehead

Picture this: it is the earliest days of America, pre-emancipation, and you are confined to a life of bondage on a cotton plantation in the Antebellum South. Your only hope of escape is rumor of a train that courses deep underground — restlessly chugging through a labyrinth of stone-walled tunnels — which is said to provide passage north. There is one catch, however: you don’t know where the train is headed next or “what waits above until you pull in.” Which is to say: freedom is coming, but with a few provisions. That’s the premise of Colson Whitehead’s latest treatise, The Underground Railroad: a 300-page novel that follows Cora, a young slave who flees Georgia for more liberated pastures (the Carolinas, Tennessee, and finally Indiana) and is trying to outrun the present.

A surrealist take on this country’s most horrific iniquity, it is a book fattened with the hopes and horrors of the American empire, and the result is nothing short of a revelation. The Underground Railroad dazzles and shocks in unexpected flashes, yet never avoids the blood-stained truths that haunt us still. The book, too, asks something more: What does it mean to make your way through the darkness even when you don’t know what’s on the other end? When I reached Whitehead — who is 46 and has published seven books to great acclaim — by phone in early August, I was curious as to how, post publication, he was balancing the novel’s increasing popularity with the fact that it is a story firmly rooted in black suffering. Simple, he said. “It tells the truth.”

COLSON WHITEHEAD: The actual slave narratives served as the foundation for the book, some of the most famous ones being Frederick Douglass’s and Harriet Jacobs’s. Harriet Jacobs was a slave in North Carolina and hid seven years in an attic until she could get safe passage out. That was the inspiration for the North Carolina section [of the book]. The U.S. government paid writers to interview former slaves in the 1930s. These were people who had been on the plantation when they were kids or teenagers. Writers collected these oral testimonies — some of them are a paragraph long, some are ten pages — and they gave me a real foundation with regard to the variety of slave life.

I didn’t see any particular value in doing a straight historical novel. The use of certain fantastical elements was just a different way to tell a story. If I stuck to the facts then I couldn’t bring in the Holocaust, and the KKK, and eugenic experiments. I was able to achieve a different effect by altering history. Instead of sticking to what happened, it was being more concerned with what might have happened. So, the North Carolina section seems like this fantastic, alternate universe ruled by white supremacy, but Oregon was founded on white-supremacist principals — it was a place for whites to go and be away from the South, which had been overrun with slaves and revolt. While the political scheme of North Carolina seems fantastic, it’s actually an echo to how Oregon was founded.

At world’s fairs and carnivals in the 1800s, white enslavers would take black people and dress them up in so-called “jungle clothes” and present them as “real African pygmies” — those sort of living exhibits were serious attractions. Obviously, to the modern person they seem inhuman and ridiculous and degrading, but they were entertainment. And I think, whether it’s the lynching scene in North Carolina or the Museum of Natural Wonders — it was a chance to engage different notions of entertainment or history being perverted as entertainment or the covering up of history.

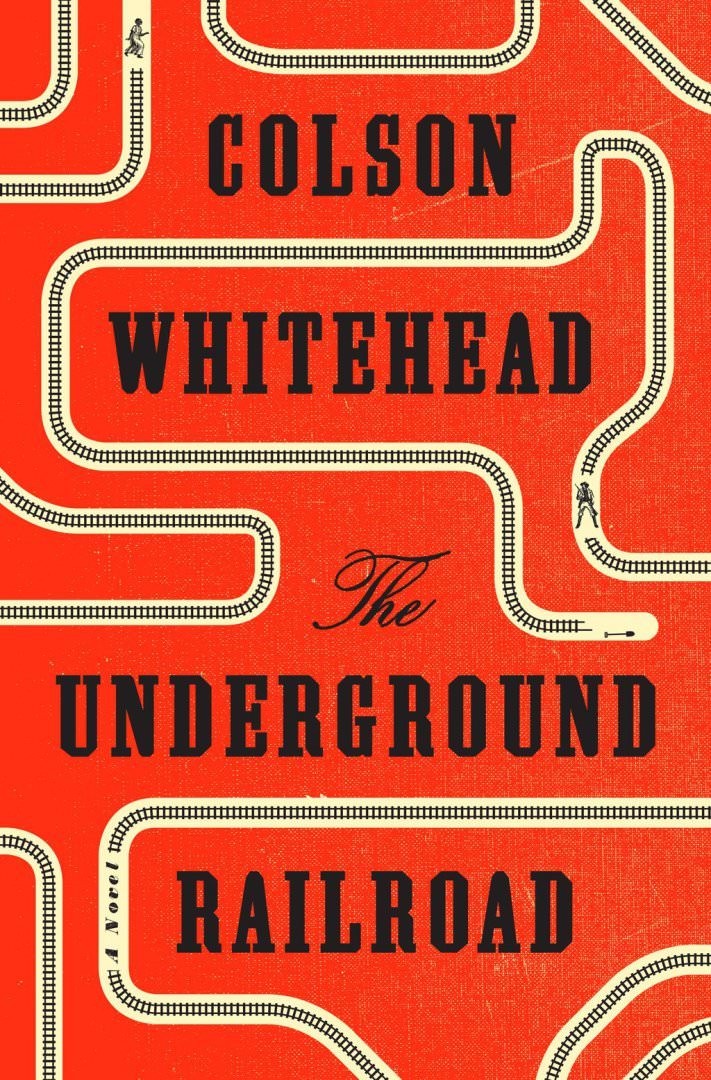

Courtesy Doubleday

Courtesy Doubleday

“We don’t generally want to contemplate slavery in any serious way. Each generation has its reckoning with history.”

In terms of the mission, with Georgia, which is the most realistic section, I wanted it to be as truthful as possible and not diminish the slave experience. And to be truthful to what happened to my family when they arrived here. I can trace some branches, maybe a hundred years back. Before 1900 it’s all pretty shady. I know some of them came from Florida and Virginia — and how did they end up there? Did they come through Massachusetts, did they come through the Caribbean? I’m leery of using the word mission, I did want to honor their experience and the other slaves who I read about in my research. This nation was founded on misery, torture, and genocide. I’m not exaggerating how this nation was formed. If you can find a different way to tell a common story — hopefully people will recognize it as their own, even if it’s not very nice to look at. I wanted to create a portrait of America, using history that is not well-known or acknowledged, whether I’m talking about the Tuskegee syphilis experiments or something else — how can we reconcile our ideas about America as an elevated nation with the true facts about our national biography?

People are saying: “Roots has been rebooted,” “There’s the TV show Underground,” “There’s 12 Years A Slave” — but those are actually exceptions. We don’t generally want to contemplate slavery in any serious way. Each generation has its reckoning with history. There’s a reckoning now with writers and showrunners in their thirties and forties, who are choosing race as a subject or slavery as a subject. It goes in waves. As someone in the process, I can’t necessarily step out and think why, why now, or what’s motivating people to come to these things.

How Cora, [the protagonist], perceives the railroad evolves throughout the book. When she first gets down there, the conductor says, “If you look outside, you can see America,” and of course, all she sees is blackness. Anytime she gets on the train, she thinks about that — if it’s sincere, if it’s a joke. In the end, she ends up making her own way in the darkness; and so, it’s sincere and sort of a grim joke. More than anything, the book is a comment on history. I take too many liberties to say it’s a document. Being able to play with time and different historical episodes allows me to, hopefully, tell a different story of America than the one it tells itself.