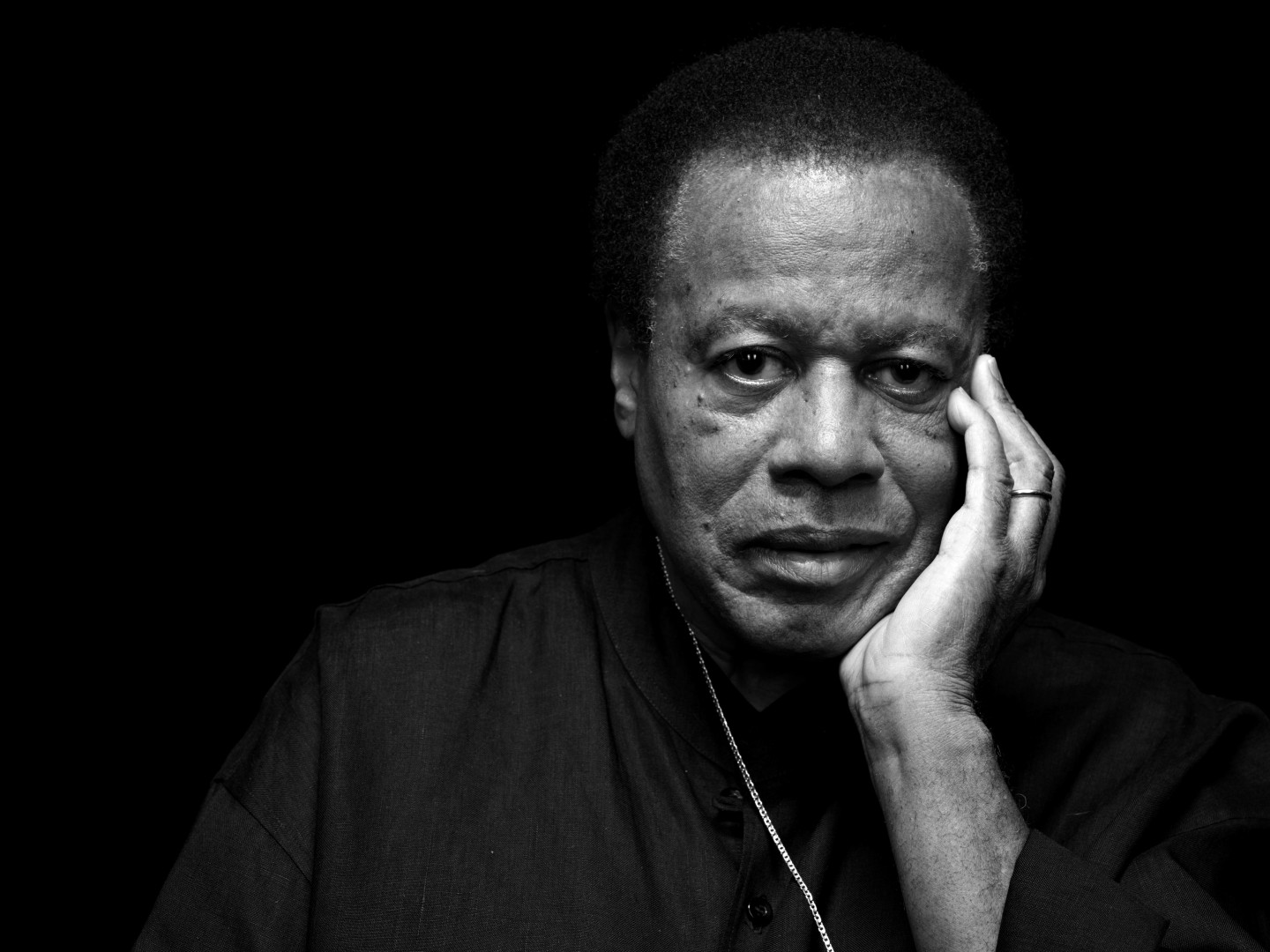

Robert Ascroft

Robert Ascroft

There comes a time in every great artist’s life when all the lessons they’ve learned go out the window and everything starts flowing on raw emotion. For Wayne Shorter, one such moment occurred during a 1965 set with Miles Davis’ Second Great Quintet at The Plugged Nickel in Chicago. The song was “Stella By Starlight,” and Shorter was tasked with taking a tenor sax solo following a breathtaking, six-and-a-half-minute treatise from Miles’ trumpet. He entered slowly (as one tends to when faced with a challenge of that magnitude), leaving long pauses between brief runs that lacked the virtuosic flair of his bandleader’s. Taken together, though, they make for three of the greatest musical minutes of all time, as close as one can come to hearing the interior monologue of a genius as pure sound, unrestricted by the limitations of language.

Shorter remembered that solo in a 1985 interview with Greg Tate as a time when “all of a sudden all of the training and everything didn’t mean nothing.” Not to be confused with improvising mindlessly — something any jazz soloist with chops can pull off — this was an act more akin to a first love: “You don’t just let your hands go anywhere because that means you know how to play,” he clarified. “But to play a horn like you’re with a girl you want to talk with and you act like you’ve never been on a date before. To make out like she’s the only one you ever talked with.”

In his 89 years on earth, Shorter breathed rarified air into the tenor and soprano saxophones, with a fusion of technique and imagination rivaled only by an ultra-shortlist of the greatest players in history. And within the jazz genre he nominally called home, he crossed paths and collaborated with nearly every other musician in that number. But his true superpower was the selective amnesia that allowed him to forget the infinite wealth of musical knowledge swirling around his brain and play as if for the first time.

Born and raised in Newark, New Jersey, he and his brother Alan were proud outcasts in high school, listening to hard bop when most kids were bumping Bull Moose Jackson, obsessing over Marvel comics and science fiction films while the rest of his class got their rocks off to the funny papers and B comedies. Even the visionary writer and cultural critic Amiri Baraka, who went to high school with Shorter, remembered him as an oddball, fondly recalling the creation of a new local longhand for things that were strange: “Weird as Wayne.”

Shorter wore those interlocking Ws like an insignia emblazoned across his chest, painting “Mr. Weird” on his saxophone case. At the early gigs of his and Alan’s band The Group — fronted by a musically illiterate singer dressed up as Dizzy Galespie — they wore baggy suits and silly shoes, putting newspapers or blank pages on their music stands as an inside joke on the audience.

These antics belied the fact that Shorter’s mind was admired, respected, and even envied by the titans who shared his bandstand, including Davis, Herbie Hancock, and Art Blakey. In his mid 20s, he joined Blakey’s Jazz Messengers and stuck around for half a decade, until Davis poached him to step into a position previously held by John Coltrane. He helped inaugurate what is considered Davis’ Second Great Quintet (1964–68), with Hancock on keys, Ron Carter on bass, and Tony Williams on drums. Together, they released six studio albums, with Shorter taking on a significant share of the composing work, leading Hancock to refer to him as “the master writer, to me, in that group.” His contributions were even more pronounced live, culminating in that multi-set marathon at The Plugged Nickel.

Even as he thrived in the jazz equivalent of The Avengers, he was embarking on a breathtaking run of 11 Blue Note releases that cemented his solo career as a superhero. Among these are Speak No Evil — which features his first wife Teruko Nakagami on the cover and contains a gorgeous cut called “Infant Eyes” dedicated to their daughter Miyako — and Adam’s Apple, which includes his best-known contribution to the jazz songbook: “Footprints.”

After the Quintet’s official disbandment, Shorter continued to collaborate with Davis, switching from tenor to soprano for the experiments of Filles de Kilimanjaro, In a Silent Way, and Bitches Brew — the records that created the foundations of what we now call fusion. And he pushed the form forward through recordings with Hancock’s V.S.O.P. quartet (essentially Miles’ Second Great Quintet redux), as his own group, Weather Report, began to gather steam.

Still arguably the group most identified with the ethos of fusion, Weather Report was both extremely of its time and generations ahead. The group’s peak form — with Shorter on soprano sax, his co-founder Joe Zawinul on keyboards and modular synths, wunderkind Jaco Pastorius on fretless bass , Alex Acuña on the kit, and Manolo Badrena on auxiliary percussion — manifested on Heavy Weather, a pinnacle of maximalist production and joyful, open harmonies that went platinum against all odds.

Outside the group, he released Native Dancer, a one-off project featuring the angel-voiced Brazilian singer Milton Nascimento that remains one of the most stunning cross-continental collaborations of all time; played the unforgettable tenor sax solo on Steely Dan’s “Aja”; and began a quarter-century creative partnership with Joni Mitchell. He won his first Grammy (for Weather Report’s “8:30”) in 1980, and went on to win 10 more.

Weather Report disbanded in early 1986, an amicable split between Shorter and Zawinul, though partly precipitated by the decline of Pastorius’ mental health. (He died less than two years later from injuries suffered in an altercation with a martial arts expert outside a Florida bar.) But Shorter continued to work tirelessly as a soloist and collaborator. Following Davis’ death in 1991, he reunited with the Second Great Quintet for a tribute album, with Wallace Roney stepping into Davis’ massive shoes on trumpet. 1997’s 1+1, an album of acoustic duets with Hancock, found both artists in a mode of somber restraint uncharacteristic of their late careers.

Shorter returned to Blue Note for his last two studio albums, Without a Net and Emanon. His final release — a live quartet album recorded at the 2017 Detroit Jazz Festival and featuring Esperanza Spalding, Terri Lyne Carrington, and Leo Genovese — arrived this past September.

Robert Ascroft

Robert Ascroft

As remarkable as his resume was, it’s far from the full story. Capturing the essence of Wayne Shorter in text is, of course impossible: One could describe his painstakingly chiseled song sculptures, his crystalline attack, his uncanny ability to transmit specific yet complex emotions into a listener’s brain, and still fall embarrassingly short.

Nearly 40 years later, Greg Tate’s 1985 interview is still the closest any writer has gotten to the core of what Wayne was all about. Published in his 2016 collection Flyboy 2: The Greg Tate Reader, it’s not a gushing longform profile but a roughly 2,500-word Q&A. Tate’s input is limited to a three-paragraph introduction, two simple questions, and a sentence-long endnote. Basically, he lets Wayne cook, which is the only reasonable thing to do.

Throughout the interview, Shorter’s genius shines through as he engages in lighthearted self-mythologizing, cementing his superhero status with every quotable gem that passes through his lips. “My brother Alan and I, we’d sit in the kitchen at a round table making Captain Marvel and Captain Marvel Jr., the Frankenstein monster, the Wolfman,” he remembers early on in the conversation, before Tate even asks his first question. “One time we tried to make the whole world.”

Still unprompted, he continues to tell his origin story, likening himself (in the third person) to a Peter Parker-like misfit. “Cat used to walk the halls and never be with a girl,” he says. “Always walked the wall. No books. You say, ‘Where your books, man?’ He says, ‘In the locker. Lost the key, forgot the combination.’”

Tate tells Shorter at one point that he’s surprised at his loquaciousness, given the somber, philosophical demeanor he’s assumed in past interviews and the supernatural intensity with which he plays. “I’m just as gregarious as these eggs,” Shorter responds. “Do you mind if I partake? I’m gonna do like when I was in school — listen to the radio, do homework, watch TV, talk on the telephone, still get an A.”

Other than that, Tate’s only remark is regarding Shorter’s unmatched attention to detail, and Shorter’s response sheds light on his whole world view. “I guess I see that the littlest thing equals the big thing,” he explains. “The little thing has got to be in there, all the details got to be in there. I like this phrase: A million dollars can’t exist without one penny, but one penny can exist without a million dollars.”

“The word ‘jazz’ to me only means ‘I dare you.’”

Elsewhere — between musings on South African apartheid, J.A. Rogers’ Race and Sex, and Lord Dunsany’s The Charwoman’s Shadow (“a baaad book”) — Shorter offers some pithy thoughts on the concept of jazz: “The word ‘jazz’ to me just means ’No Category,’” he says. “It’s an intangible word.” This sort of statement became a calling card for Shorter, who seemed to hold jazz in a different category than other genre signifiers like rock ’n’ roll. “The word ‘jazz’ to me only means ‘I dare you,’” he told The New York Times nearly 30 years later.

It’s interesting that Shorter — someone who helped change the face of jazz by broadening its sights — still seemed to have such fondness for the word as he approached the end of his life. As a new generation of artists rejected the signifier as racist and reductive — not an entirely novel position but one recently championed by New Orleans trumpeter Nicholas Payton, who coined the term “BAM” (Black American Music) as a more inclusive and historically accurate alternative — Shorter continued to express a childlike wonder at jazz’s mystical capacity.

On closer examination, though, Shorter’s stance makes perfect sense: Jazz was his superpower, and he viewed it that way — not as an end but as a means. Like flight, invisibility, or a sixth sense, it has earth-shaking potential, but only in the right hands.